.

Health Implications

We are bombarded with messaging around how and why sugar is bad for us, with varying positions and recommendations on how we should improve our diet. There is a lot of information, including conflicting information from sources of varying credibility and interests, on this controversial topic. This article provides education and historical context on key categories of sugar, an overview of published guidance on sugar intake, and some commentary on potential health implications associated with refined sugar. These views are based on my research and personal experiences with both completing and coaching others through the “14 Day No Refined Sugars + Grains Challenge.”

Note: Clean Culinary Canvas does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a substitute for medical advice, and you should not take any action before consulting with a healthcare professional.

Sugar Education and Historical Context

Carbohydrates are naturally occurring sugars, starches, and fibers found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, and dairy. In terms of chemical structure, all carbohydrates are made up of sugar molecules. Sugar comes in many different forms and goes by many, many names!

Carbohydrates are naturally occurring sugars, starches, and fibers found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, and dairy. In terms of chemical structure, all carbohydrates are made up of sugar molecules. Sugar comes in many different forms and goes by many, many names!

Monosaccarides or “simple sugars” are single-sugar molecules such as glucose, fructose, and galactose. Once consumed, both glucose and fructose are directly absorbed into the bloodstream. As blood glucose levels rise, the pancreas is triggered to release insulin into the bloodstream. Insulin moves glucose from the blood and into cells for energy & storage. On the other hand, fructose must move from the blood and into the liver for metabolization before it may be used by the body. The liver metabolizes fructose into glucose, lactose, and glycogen, where the glucose is then further metabolized for energy. If the body has sufficient glucose, the liver will simply store fructose as fat.

Disaccharides are two simple sugars linked together. Examples include sucrose or “table sugar” (glucose + fructose), lactose or “milk sugar” (glucose + galactose), and maltose or “malt sugar” (glucose + glucose). Once consumed, disaccharides must be broken down into simple sugars before they may be used by the body. Enzymes in the mouth begin to break down sucrose into glucose and fructose. The majority of this sugar’s digestion occurs more downstream and in the small intestine from where the resulting simple sugars are then released into the bloodstream.

Sucrose (glucose + fructose) naturally occurring in fruit and honey have been part of the human diet for millennia. Sucrose made by processing sugar cane and sugar beets has been part of our diet for centuries. However, sucrose poses technological limitations in select modern food manufacturing applications. This granulated ingredient often needs to be dissolved before use. It is prone to hydrolyze within acidic systems, altering the sweetness and flavor profile of certain foods. Beyond this, sugar cane and sugar beets are grown in equatorial regions associated with political and climatic instability, posing supply risks.1 In 1974, the price of table sugar skyrocketed by >300%, representing the highest price hike across all food categories in the US!2 This drove the rapid adoption of a low-cost alternative: high fructose corn syrup (HFCS). HFCS is a liquid fructose-glucose sweetener made by processing corn. Specifically, corn is milled into cornstarch and then further processed into corn syrup. Corn syrup is primarily comprised of glucose. This liquid syrup is then treated with enzymes to convert approximately half of the glucose into fructose.1 Compared to sucrose, HFCS is cheaper, easier to make, associated with a longer shelf-life, and sweeter. Since its introduction into the modern diet, HFCS has made its way into the majority of packaged foods and beverages.1,3,4

Summary

- Glucose and fructose are absorbed directly into the bloodstream. Glucose is burned for energy or stored as glycogen (molecular chains of glucose). Fructose moves onto the liver where it is converted to glucose for energy or stored as fat.

- Sucrose (table sugar) and processed alternatives such as High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) contain nearly equal parts of glucose and fructose. These must be broken down into simple sugars (glucose and fructose) before they may be used by the body.

- HFCS was introduced into the modern diet in the 1970s. It is highly prevalent in packaged foods and beverages.

Sugar Intake

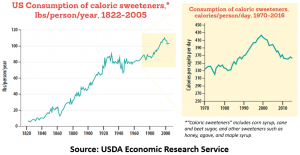

In the United States, average sugar consumption has been on the rise for over a century, with a notable spike following the introduction of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in the 1970s.

the United States, average sugar consumption has been on the rise for over a century, with a notable spike following the introduction of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in the 1970s.

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends no more than 6 teaspoons (25 grams) of added sugar per day for women and 9 teaspoons (38 grams) for men.3 The US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) participates in the development of Dietary Guidelines for Americans that recommends limiting added sugar intake to less than 10% of total calorie intake per day.4 For a 2,000 calorie per day diet, this amounts to 200 calories or 50 grams of added sugar.

The average American consumes 82 grams of added sugar per day (16% total calorie intake), which is well over the recommended daily value.6 FDA recently launched a Nutrition Innovation Strategy defining actions to reduce preventable death and disease related to poor nutrition, including excessive sugar intake. As part of this strategy, information on added sugars is now required on Nutrition Facts labeling. Labeling reflecting added sugars that contribute to 5% or less of the recommended Daily Value (DV) are considered low sources of added sugar, whereas anything above 20% are considered high sources of added sugar.7

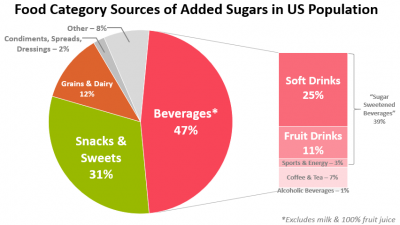

The majority of sugars in a typical American diet include sugars added to foods during its processing or preparation for taste, extended shelf-life, and appearance.4 These processed foods and beverages typically contain high levels of added sugar making it very easy to exceed recommended daily limits. For example, a 12 oz. can of soda contains 11 teaspoons (46 grams) and a standard cup of flavored yogurt includes 7 teaspoons (29 grams).8 The charts below detail food category sources of added sugars within the US population.

Source: 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans4

As significant amounts of refined sugars such as HFCS are added to packaged foods and beverages, putting emphasis on the reduction of refined and processed sugars and foods can help to effectively reduce overall sugar intake within recommended ranges.

Summary

- The recommended Daily Value of added sugar intake is less than 10% of total calorie intake per day. For a 2,000 calorie diet, this amounts to 200 calories or 50 grams of added sugar per day.

- Information on added sugar content is now required on Nutrition Facts labeling.

- As significant amounts of refined sugars such as High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) are added to packaged foods and beverages, putting emphasis on the reduction of refined and processed sugars and foods can help to effectively reduce overall sugar intake within recommended ranges.

Health Implications

FDA receives many inquires on the safety of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), where several cite observations on differences between how the human body metabolizes fructose and other simple sugars.9 To evaluate the effects of HFCS and fructose, researchers have studied subjects fed diets high in HFCS, fructose, and glucose. Many of these studies conclude that fructose is more harmful than glucose, pointing to negative physiological outcomes including increased abdominal fat; increased blood cholesterol and triglycerides; and increased rates of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. However, these studies are confounded by the influence of added sugar, irrespective of sugar-type. Current evidence across review articles and metanalyses indicates that moderate fructose consumption is not harmful.8, 10,11,12 Beyond this, sucrose and HFCS contain approximately equal amounts of fructose and glucose and are admittedly essentially chemically identical. A 2013 review article published by Advances in Nutrition concludes that the human body recognizes and digests both the same, where there is no evidence to say that one impacts our metabolism or disease risk more than the other.13 The US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) holds these same views, where they support recommendations to limit the consumption of all added sugars, including HFCS, sucrose, and fructose, as discussed in the previous section.4,9

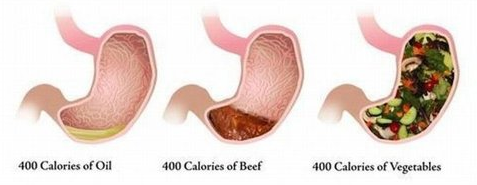

It is important to note that although the human body’s response to chemically identical sugar types does not depend on if they are naturally present or added to foods, sugars found naturally in foods are part of a package of nutrients and dietary fibers. The refining process strips foods of water, fiber and other nutrients, leaving behind sugar and only sugar. This extraction is more calorie dense compared to its original state.

Caloric Density

Satiation is the feeling of fullness achieved from food consumption. Our stomachs are lined with stretch and density receptors. These gastric receptors are triggered by the presence of food. Once triggered, these receptors stimulate neuronal pathways to the brain signaling satiation and appetite reduction.14,15 As shown in the figure below, calorie dense foods (foods containing “empty calories”) such as oils and meats leave the stomach empty and the brain wanting to eat more. Whole plant foods are typically high in fiber content, where fiber soaks up water, expands, and engages gastric stretch receptors. These foods trigger satiation and a feeling of fullness, where we are not triggered to consume more than we need to.14,16

Source: Julieanna Hever, MS, RD, CPT, Illustration by Sherri Nestorowich16

HFCS is prevalent in packaged foods and beverages. Although there is no evidence indicating risk around how this form of sugar is recognized and metabolized by our bodies, processed foods typically contain excessive amounts of added sugar stripped from other essential nutrients and dietary fibers. Beyond this, foods associated with high added sugar content are often also high in added fats, sodium, and refined flours, making these unhealthy for a variety of reasons.14 These calorie-dense, processed foods have been shown to produce cravings, withdrawal, and chemical changes in the limbic system (“the brain’s reward center”).8,18 The potential for over consumption of sugars in the form of processed foods and beverages coupled with overeating triggered by such calorie-dense foods makes targeting refined sugars as a source of excess, dense calories a prudent diet strategy.

Summary

- The metabolic and health effects of various sugars are controversial and the subject of intense scientific debate.

- The potential for over consumption of sugars in the form of processed foods and beverages coupled with overeating triggered by such calorie-dense foods makes targeting refined sugars as a source of excess, dense calories a prudent diet strategy.

.

References

1 White, John S. (01 December 2008). “Straight Talk About High-Fructose Corn Syrup: What It Is and What It Ain’t.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 88 (6), 1716S-1721S. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/88/6/1716S/4617107.

2 Barnum, Isadore. (15 November 1974). “Soaring Sugar Cost Arouses Consumers and U.S. Inquiries.” New York Times. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/11/15/archives/soaring-sugar-cost-arouses-consumers-and-us-inquiries-what-sent.html.

3 Johnson, R. K., Appel, L., Brands, M., Howard, B., Lefevre, M., Lustig, R., Sacks, F., Steffen, L., & Wyllie-Rosett, J. (15 September 2009). “Dietary Sugars Intake and Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association.” Circulation, 120 (11), 1011-20. Accessed 12 June 2020. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/120/11/1011.full.pdf.

4 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2020). “2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.” 8th edition. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf.

5 Healthy Food America. (2020) “Sugar Advocacy Toolkit.” Accessed 12 June 2020. http://www.healthyfoodamerica.org/sugartoolkit_overview.

6 Guthrie J. F. and J. F. Morton. (1 January 2000) “Food Sources of Added Sweeteners in the Diets of Americans.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 100 (1): 43‐50.

7 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (March 2020). “Added Sugars: Now Listed on the Nutrition Facts Label.” Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/135299/download.

8 “How Much is Too Much? The Growing Concern Over Too Much Added Sugar Within Our Diets.” Sugar Science, University of California San Francisco. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://sugarscience.ucsf.edu/the-growing-concern-of-overconsumption.html#.XuUH4-d7m00.

9 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (4 January 2018). “High Fructose Corn Syrup Questions and Answers.” Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/high-fructose-corn-syrup-questions-and-answers.

10 Khan, T A and Sievenpiper, J. L. (2016). Controversies About Sugars: Results from Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses on Obesity, Cardiometabolic Disease and Diabetes. European Journal of Nutrition. 55 (Suppl 2): 25–43. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5174149/pdf/394_2016_Article_1345.pdf.

11 White J. S. (2013). Challenging the Fructose Hypothesis: New Perspectives on Fructose Consumption and Metabolism. Advances in Nutrition. 4(2): 246–256. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3649105/pdf/246.pdf.

12 Gearing, Mary E. (5 October 2015). “Natural and Added Sugars: Two Sides of the Same Coin.” Harvard University: Science in the News Blog. Accessed 12 June 2020. http://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2015/natural-and-added-sugars-two-sides-of-the-same-coin/.

13 Rippe, J. M. and T. J. Angelopoulos. (March 2013). “Sucrose, High-Fructose Corn Syrup, and Fructose, Their Metabolism and Potential Health Effects: What Do We Really Know?” Advances in Nutrition. 4(2): 236–245. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://academic.oup.com/advances/article/4/2/236/4591632.

14 Fulkerson, Lee, John Corry, Joey Aucoin, Neal D. Barnard, and Gene Baur. Forks Over Knives. New York: Virgil Films, 2011.

15 Wilde, P. J. (2009). “Eating for Life: Designing Foods for Appetite Control.” Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 3 (2): 366–370.

16 Hever, J (8 October 2013). “Losing Weight on a Vegan Diet.” Plant Based Dietitian, Julieanne Hever. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://plantbaseddietitian.com/losing-weight-on-a-vegan-diet/.

17 Todd, Carolyn. (24 June 2007). “Can Our Bodies Even Tell the Difference Between Naturally Occurring and Added Sugars?” Self. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.self.com/story/how-different-are-naturally-occurring-sugars-really-from-added-ones.

18 Avena, N M, Rada P, and B G Hoebel. (2008). “Evidence for Sugar Addiction: Behavioral and Neurochemical Effects of Intermittent, Excessive Sugar Intake.” Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews. 32 (1): 20‐39. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2235907/.